News

Air Transport As A Vehicle for Sustainable Development

"Take a short break with ENAC Alumni summer issue and discover articles from our previous mag"

Introduction

For many years, and increasingly over the past few months, mainly in Europe, air transport has often been presented in the press, media and social networks as a sector with an increasingly negative impact, which must be restricted, either by increasing taxes or by making passengers feel guilty[1].

A caricature of air transport is often given, reducing it to an activity that enables wealthy customers to fly several thousand kilometres for a week-end away, with no consideration for their impact on the environment. Yet air transport is actually a much more comprehensive and diverse commonplace activity. Therefore, it seems we need to provide the most objective assessment possible on how air transport fits in (or does not fit in) with a sustainable development approach. This special report does not claim to provide all the answers to current and future social challenges, but it does present some key points from major sector stakeholders, industry experts, regulations authorities and independent consultancy firms working on airline carbon strategies and operation optimisation tools.

Enjoy reading this special report and we hope to be able to launch comprehensive and continued constructive discussions on this essential subject, so as to share data and find solutions together.

Reality and Perception

When we talk of sustainable development, we need to look back at the original definition given in 1987 by the Brundtland Commission in its "Our Common Future" report. It defines sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."[2]

As you can see, this concept does not talk about taking a step backwards - to the contrary, it is about development! However, this development must not just be economic, it must also consider the consequences and impacts (both positive and negative) on the environment and society at large, as well as their interactions. This is what we call the externalities of an activity. Companies are increasingly being asked for a strategy and action plans to internalise their externalities, i.e., to take responsibility for the consequences (particularly the negative ones) of their activities via mitigation, offsetting and adaptation measures.

The notion of "need" as the basis for defining the sustainable development concept suggests that we can assess various current needs wherever we are on the planet (particularly in developing countries where basic needs are not always met) and provide an efficient response. This process must be able to take place constantly, now and any time in our future. This means we have to permanently evaluate the needs of future generations to assess whether the responses we are providing today are not going to become obstacles, so as to find and implement solutions for our future challenges. In essence, this concept has no geographical or time-related borders.

An aircraft manufacturing programme can run over more than half a century: from designing a type of aircraft in order to meet airline expectations to reaching the end of an aircraft's service life and recycling the last aircraft of this type, through manufacturing, commissioning, operating (via different airlines, often in different countries and continents), maintaining and developing certain systems. This activity is therefore fully in line with the concept of sustainable development, since a single aircraft must be able to be used beyond national or continental borders, going from one operator in Asia to another in Europe or Africa for example, throughout its long service life. It is therefore important to be able to plan for future needs and expectations from airlines but also end consumers, i.e., passengers or companies requiring goods to be transported (cargo business) or even to be able to respond to an emergency medical or health request.

However, what has become commonplace transportation, with over 4 billion passengers and 35% of goods (in terms of value) transported in 2018,[3] today is still seen by many people as a sector used for tourism and leisure travel (and therefore considered non-vital). Worse still, the emergence of low-cost airlines, making air transport accessible to more people (reduction of inequalities) is often singled out for generating additional demand and therefore resulting in increased traffic.

In a world where climate change is a reality and man-made CO2 emissions keep on growing (the threshold of 415 parts per million (ppm) was exceeded for the first time in the history of mankind on 17 May 2019), air transport, which is highly dependent on liquid carbon fuels and therefore produces CO2 emissions, is regularly attacked from several angles:

- Although the overall emissions from international air transport only account for 2.5 to 3% of human-generated emissions, as explained by Stéphane Amant (carbone4) in his article, this proportion could greatly increase if all other sectors were able to reduce their carbon footprints in line with the commitments of the Paris Agreement and if the air sector were to continue to grow by 4.4% a year over the next 20 years (source: Airbus Global Market Forecast) without a drastic change to the technology, fleet composition and operations,

- As air traffic is mainly an international business, it cannot be treated like fixed activities by each Member State in the UN Framework Convention On Climate Change (UNFCCC). It is managed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the UN agency specialised in international civil aviation. As such, many people think that air transport is excluded from international agreements (Kyoto protocol, Paris Agreement) and therefore benefits from preferential treatment. The reality is that the emissions linked to a State's domestic aviation are listed by the State in question as part of the UNFCCC, whilst international aviation is governed by the ICAO,

- The fuel used by aviation is tax-exempt and this makes it a privileged sector compared to road transportation, for example. As indicated above, domestic air routes are managed by the States and governments in question, and they are able to make decisions on the subject. For example, Brazil, the US, India and Switzerland have established tax for domestic flights. For international traffic, this exemption comes under the bilateral agreements established between each country that signed the Chicago Convention[4] (first version in 1944).

The Chicago Convention, as clearly indicated in its preamble, was established, considering that "the future development of international civil aviation can greatly help to create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world" and "it is desirable to avoid friction and to promote that co-operation between nations and peoples upon which the peace of the world depends". It is recognised that generations born after the Second World War have been very lucky not to have experienced periods of widespread conflict, and consider this a given. However, keeping the peace is actually a permanent effort and the development of air transport has certainly contributed to this, favouring cultural and tourism-related exchanges, enabling these differences to coexist and encouraging mutual understanding. This is a point that you must bear in mind at a time when the first climate refugees have no other choice than to leave their home regions, which have become uninhabitable due to the consequences of global warming, and where populism is once again rearing its head, suggesting a trend for inward-looking attitudes.

A Highly-Regulated Sector

The ICAO, created by the Chicago Convention in 1944, will turn 75 in 2019. Over this relatively short period on the scale of human existence, the organisation "works with the Convention’s 193 Member States and industry groups to reach consensus on international civil aviation Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) and policies in support of a safe, efficient, secure, economically sustainable and environmentally responsible civil aviation sector"[5]. For over 50 years, the ICAO has been working with the international community to define increasingly stringent standards in terms of noise and emissions management. This approach to planning, implementing, assessing the impacts of and defining a more ambitious standard is fully in line with a continuous improvement approach consistent with the social responsibility measures, based on the Deming cycle[6]. A technical committee, a special body of the ICAO Council was created in 1983 under the name of the Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP) to perform technological and economic analyses and assess the social impact of the measures proposed (for approval by the Council) and ratified by the ICAO Assembly. These different standards, but also practices such as a balanced approached to operational noise management, are included in Annex 16 of the Chicago convention[7].

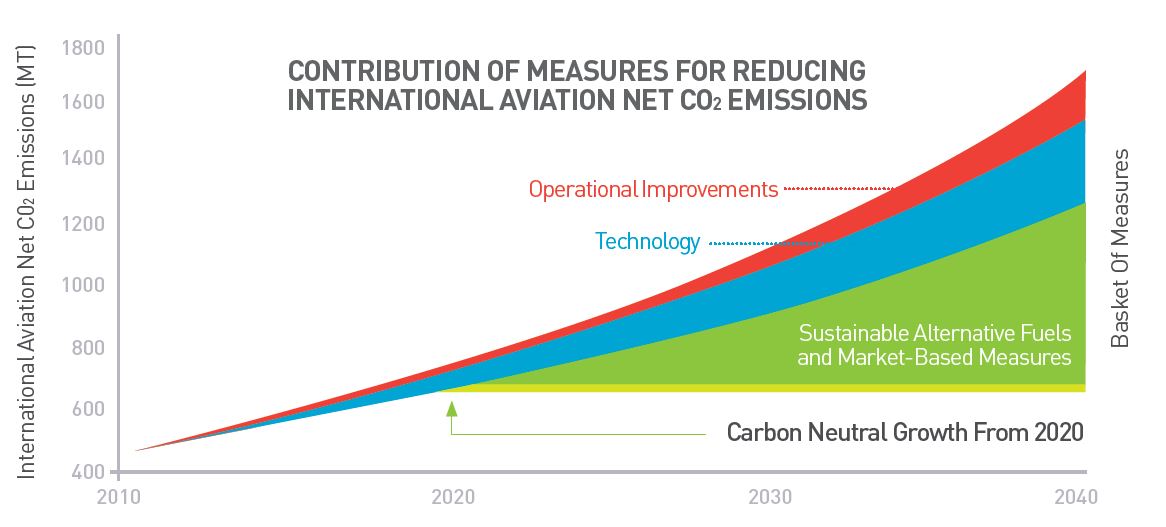

The theme of climate change (and therefore CO2 emissions) is one of the major challenges for the sustainable development of air transport. This is because, even if it only accounts for 1 of the 17 sustainable development goals defined and approved by the UN in 2015, its consequences and links to many other goals make it a challenge for all States and global economic players. The ICAO has established a set of measures based on 4 main areas:

- Technological improvements developed by manufacturers, renewal of aircraft fleets and development of a CO2 standard,[8]

- Optimisation of air traffic control and continuous improvement of operational performance to reduce overall traffic fuel consumption, without in any way compromising air traffic safety. For example, the Toulouse-based start-up OpenAirlines agreed to give us some illustrations on the aids they can provide to airlines to help reduce fuel consumption based on analysis and precise data processing,

- Development and deployment of alternative sustainable fuels, thus reducing the dependency on fossil fuels,

- Measures based on the market and notably the first global sector-specific mechanism to offset emissions (CORSIA) for which the ICAO has agreed to prepare a descriptive article for our special report.

A Sector Facing Up to its Responsibilities

Although the ICAO has greatly contributed to promoting the improvement of environmental performance for air transport via recommended practices and standards, industry and sector professionals have not been resting on their laurels by any means. Therefore, current aircraft are 80% more effective in terms of fuel consumption (and therefore CO2 emissions) and 75% quieter than 50 years ago. In half a century, the sector has multiplied its research programmes to enable these remarkable improvements, which are doubtlessly unequalled in many other sectors. These improvements are even more impressive as they are the result of constant compromises including technical acoustic improvements competing with the improved specific consumption. The search for an optimum point is still the ultimate goal.

At the same time, air traffic has considerably developed, becoming an essential tool for the global economy and globalised supplier chains, and a commonplace mode of transport. Indeed, if nothing else were done and despite the inherent progress made, global CO2 emissions would keep constantly increasing, as specific improvements are not enough to offset the increase in traffic. For this reason, certain stakeholders consider that the best way to reduce the impact of air transport on the environment is simply to reduce activity in the sector. This stance, albeit respectable, does not consider the negative effect this reduction would cause on the whole economy and global social exchanges, nor the impact generated by one or more replacement activities. For example, someone deciding not to go on a weekend trip to the other side of Europe to limit their CO2 emissions would not necessarily spend the weekend at home, performing no CO2-generating activities (such as car journeys or the use of various electronic or IT tools which often have an underestimated impact).

It would therefore appear more relevant to find technical, organisational and financial solutions to separate the increase in air traffic from its associated emissions, enabling the sector to keep meeting current and future needs as best it can. Therefore, via the Air Transport Action Group (ATAG), the whole sector has joined forces and has adopted an ambitious common commitment from 2008, based on three objectives:

- A technological improvement of 1.5% per year from 2009 to 2020,

- A carbon-neutral increase from 2020,

- A 50% reduction in the overall CO2 emissions of the sector compared to 2005.

These commitments, made ten years ago, made it one of the first sectors to collectively agree to an overall approach, allowing each branch of the sector the possibility to go further if possible: therefore, technological improvement has exceeded 2.1% per year for the period and airports have committed to a carbon accreditation scheme at the same time - today almost 300 airports have passed this independent check of their carbon performance[9].

Moving On

Although the climate change challenge is one of the biggest (or the biggest) of modern society, and air transport in particular, assessing how the sector is part of a sustainable development approach may not and must not be limited to this criterion alone. Indeed, it is important to determine the impacts (positive and negative) of the sector as regards the 17 sustainable development goals defined by the UN, as these goals are now a tool for assessing our sustainability performance. An initial assessment was conducted by the ATAG and can be consulted via their publication "Flying in Formation", launched in 2017[10]. In addition, the ATAG regularly assesses the development of its impacts for each of these goals, and applies this analysis with a detailed geographical focus via the publication "Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders". In this context, the ATAG agreed to present this approach via an article for our special report.

Air transport, since its origins and the Aéropostale pioneers, has succeeded in setting various new technological, geographical, time-related and societal standards over a relatively short period (it is still a young industry). Even if the sector currently provides commonplace transportation, it is not yet perceived by some as an integral part of our daily lives, probably because they still see making a machine weighing several hundreds of tonnes fly as an extraordinary exploit, in the literal sense of the term.

Although our sector is a high-tech sector, with technical experts and specialised engineers, its ability to communicate well (not only results but also improvement objectives) is still limited to date and the sector is hesitant in looking to the future and speaking about the diverse current and future research programmes. There is clearly room for improvement if the sector wants to show that it is looking to the future with as much rigour and ambition as in the past, where it was able to show impressive, recognised results. This ambition should enable the sector to gain legitimacy in terms of its purpose and attract the best talent to turn this ambition into a reality. However, this communication must go beyond technological considerations, and include irrational aspects with as much importance, to be able to satisfy them. From this viewpoint, to share best practices and try and find solutions to sustainability challenges together, ENAC Alumni has just created the Sustainable Development Circle, a new "business" circle that is accessible to all ENAC Alumni. If you have not yet signed up, now is surely the time to do so.

Please read and think about the series of contributions from the ICAO, the ATAG, Carbone4 and OpenAirlines to gain more personal insight. To conclude, I would like to leave you with a quote from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: "As for the future, your task is not to foresee it, but to enable it."

References

[1] The "Flygskam" (flight shame) movement came from Scandinavia and has already had a significant impact on air traffic, notably in Sweden.

[2] https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/sites/odyssee-developpement-durable/files/5/rapport_brundtland.pdf

[3] Source: https://aviationbenefits.org/media/166344/abbb18_full-report_web.pdf

[4] https://www.icao.int/publications/Documents/7300_cons.pdf

[5] Source: https://www.icao.int/about-icao/Pages/FR/default_FR.aspx

[6] The Deming cycle is a graphic depiction of the PDCA (plan-do-check-act) quality management method, also used for environmental management and sustainable development approaches.

[7] Annex 16 includes 4 volumes (noise, engine emissions, CO2 emissions and CORSIA) and a technical manual. https://www.bazl.admin.ch/bazl/fr/home/experts/reglementation-et-informations-de-base/bases-legales-et-directives/annexes-a-la-convention-de-l-organisation-internationale-de-l-av.html

[8] This standard is applicable to new types of aircraft certified after 2020 and types of aircraft already certified and still being produced from 2023, with an end to the production of non-compatible aircraft from 2028.

[9] Airport Carbon Accreditation: https://airportco2.org/

[10] https://aviationbenefits.org/media/166149/inside_abbb2017_atag_web_fv.pdf

Find the whole file "Air transport and sustainable development" in the Mag#25 of ENAC Alumni

2

2

No comment

Log in to post comment. Log in.